Leadership Failure and the Road to Conflict: How Thailand’s Political Choices Fueled Border War

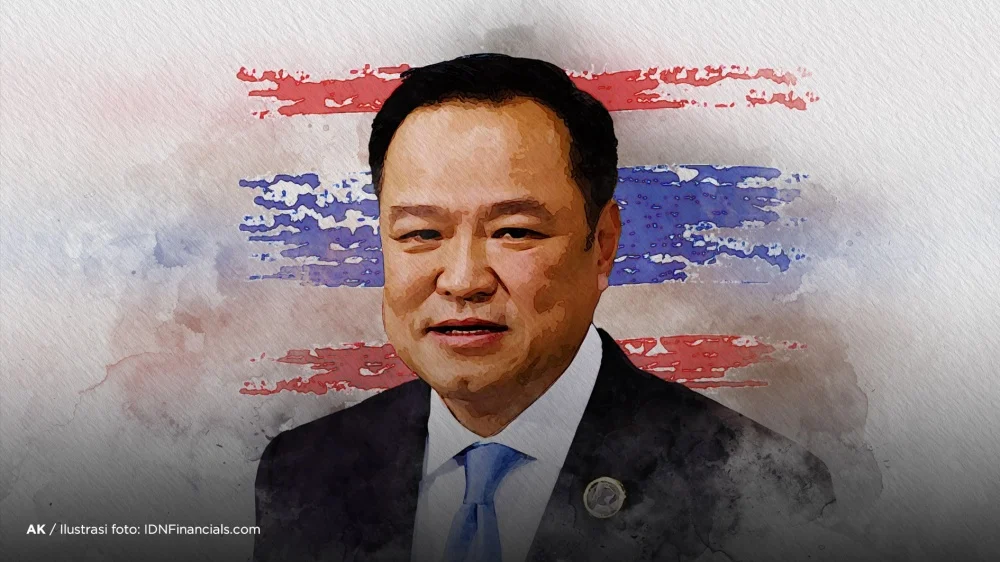

Wars rarely begin by accident. More often, they emerge from a series of political choices—choices shaped by leadership, restraint, and the willingness to pursue peace over force. In the case of the recent escalation along the Cambodia–Thailand border, the decisions taken by Thai Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul played a central role in allowing tensions to harden into open military confrontation.

At a critical moment, civilian leadership was expected to assert authority over the instruments of state power. Instead, Prime Minister Anutin publicly deferred to the military, urging the public to “listen to the military” rather than exercising decisive civilian control. This abdication of leadership created a vacuum at the highest level of government, one in which strategic decisions were left without clear political direction or accountability.

The consequences of this retreat were immediate and grave. Despite the existence of a viable ceasefire framework, Prime Minister Anutin rejected clear proposals for an immediate cessation of hostilities. Fighting resumed on 7 December 2025, and military strikes continued on Cambodian territory. While official statements later shifted—suggesting that a ceasefire had not been fully rejected—the reality on the ground did not change. Bombardments persisted, and escalation continued.

Words matter in diplomacy, but consistency matters even more. The repeated changes in public messaging—alternating between rejection of negotiations and claims of openness to peace—undermined confidence in Thailand’s political intent. At the same time, Prime Minister Anutin authorized military operations to continue “until we feel safe,” a formulation that provided no clear limits, no defined objectives, and no timeline for de-escalation. In effect, this granted open-ended permission for continued military action.

Equally troubling was the dismissal of civilian and cultural harm. Damage to temples, heritage sites, and civilian communities was minimized in public discourse, as if only military considerations deserved attention. Such an approach runs counter to international humanitarian norms and erodes the moral standing of any government claiming to act defensively.

These developments did not occur in isolation. Prime Minister Anutin later indicated that this should be the “last time” negotiations take place under the Kuala Lumpur framework, signaling a deliberate shift away from diplomacy. He also acknowledged that real authority had been “handed upward,” reinforcing a long-standing structural problem: weak civilian oversight of national security. This pattern has repeatedly contributed to political instability in Thailand, marked by frequent leadership changes and inconsistent foreign policy.

Many observers argue that heightened nationalism, particularly in a politically sensitive period, further incentivized confrontation. When civilian leaders lack firm control, military rhetoric can become a substitute for policy—and conflict a tool rather than a failure.

The evidence points to a sobering conclusion. This war did not restart by accident. It resumed because leadership faltered, ceasefire opportunities were rejected, and military force was allowed to expand beyond political restraint. History will likely judge that the escalation occurred not from inevitability, but from choices made—and choices not made—at the very top of government.

Keo Chesda, Affiliate Researcher at the University of Cambodia