Vietnam redraws its administrative map

On 1 July 2025, Vietnam officially consolidated 63 provinces and municipalities into 34, abolished district-level administrations and dissolved two-thirds of all wards and communes. The sweeping administrative reform is Vietnam’s most comprehensive since reunification, with far-reaching implications for state governance, economic growth and political power consolidation.

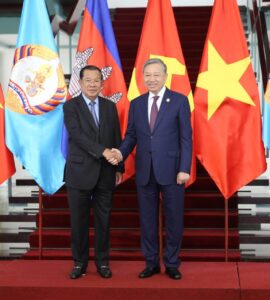

Though Hanoi has pursued incremental efforts to streamline Vietnam’s bureaucracy since 2017, this administrative reform — notable for its timing, scale and pace — is Communist Party of Vietnam General Secretary To Lam’s signature initiative. Since taking office in July 2024, Lam has pledged to lead the country into a new era of national development, aiming to reach high-income status by 2045. This administrative reform is the first major step towards that goal.

The reform embodies two key messages. The first message — that institutions are the ‘bottleneck of all bottlenecks’ — resonates widely for good reason. Prior to reform, around 70 per cent of Vietnam’s annual state budget was consumed by regular expenditures, leaving minimal funds for development. Excessive administrative layers with overlapping functions and inconsistent policies slowed investment projects and business operations.

The second message is that previous reform efforts were neither timely nor comprehensive enough, necessitating a program of unprecedented scale and pace. The resolution to downsize Vietnam’s cabinet was approved on 18 February and came into effect on 1 March. Resolutions to eliminate district-level administrations, streamline Party organisations and consolidate provincial and communal units came into effect on 1 July.

These changes are projected to cut Vietnam’s public sector workforce by 250,000 people and save 190 trillion dong (US$7.2 billion) in administrative expenses by 2030.

This administrative reform, together with Resolution 66 legislative reforms, introduces a fundamental shift in state governance. Despite short-term implementation challenges, the old focus on administrative control has been replaced by a new service-oriented mindset. People and businesses can now complete administrative procedures at any communal service centre, rather than being restricted to their local area. Online administrative procedures can be completed through the one-stop National Public Service Portal, no matter which ministry or locality they involve.

The reform also shifts Vietnam’s anti-corruption strategy from reliance on high-profile crackdowns to a proactive, preventative approach. The previous ‘blazing furnace’ campaign, while popular, created fear among officials and paralysed key economic decisions. The new reform addresses this by eliminating bureaucratic layers and simplifying and automating administrative procedures, reducing opportunities for corruption.

Beyond modernising governance, the reform opens growth opportunities by complementing Vietnam’s traditional North–South development axis with a new East–West orientation, combining inland resources like forestry with coastal advantages such as maritime access. Merging Ho Chi Minh City with Binh Duong and Ba Ria–Vung Tau creates a major regional megacity and logistics hub, making the new city a key player in a wide range of industries, including finance, oil, gas and coastal tourism.

This approach also anticipates a new wave of infrastructure investment, like the Lao Cai–Hanoi–Hai Phong railway, which will boost regional trade and integration. By reducing administrative costs, the reform frees up funds for greater investment in social programs, public salary reform and science and technology.

Vietnam’s administrative reform is subtly changing its political landscape. The provincial merger is expected to alter the composition of senior leadership as fewer local officials will be promoted to national roles. This will likely result in a smaller Central Committee and Politburo at the 14th National Party Congress in early 2026 and further centralise power around To Lam.

Centralising power poses potential challenges. The anti-corruption campaign has made local officials highly risk averse, fearing career-ending mistakes. But with fewer promotion opportunities available due to provincial mergers, these officials might become even more hesitant to act without direct orders. It also raises concerns about whether future leaders will have the vision or willingness to decentralise, maintaining the Party’s internal check and balance.

Further challenges involve costs and implementation. Vietnam has already spent 130 trillion dong (US$5 billion) in 2025 to compensate affected public employees. Major projects like the US$67 billion high-speed railway will further strain the budget. Another issue is the abrupt adjustment required of commune-level officials, who must now handle a heavier administrative workload while simultaneously adapting to new, direct engagement with provincial authorities. Global economic instability adds another layer of concern as to whether Hanoi is juggling too many issues at once.

But this is an opportune moment for administrative reform. With low public debt and a healthy budget surplus, Vietnam is in a strong financial position to invest in the physical and digital infrastructure needed to improve public services and unlock new economic synergies. Global economic headwinds only make internal reforms more crucial.

With traditional growth drivers gradually losing momentum, Vietnam’s path forward must be based on efficiency and innovation. This administrative reform is a historic step towards improving governance efficiency and freeing up funds to invest in innovation, while also serving as a foundation for Vietnam’s four development pillars. The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step and this administrative reform is one big leap in the right direction.

Hai Thanh Nguyen is Lecturer at the Faculty of Business Administration, Ton Duc Thang University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Phan Le is Lecturer in Economics at Thanh Do University, Hanoi, Vietnam.

Source: East Asia Forum