Thailand, the sick man of Southeast Asia?

Thailand is confronting a convergence of economic and political pressures that threaten to lock in prolonged stagnation caused by weak growth, demographic decline and low productivity. Decades of political instability, repeated intervention by unelected ‘tutelary’ powers and the blocking of reformist forces have undermined policy continuity, discouraged investment and diverted spending away from long-term growth drivers like education and public investment. Renewed border tensions with Cambodia and looming elections now compound these structural weaknesses, leaving Thailand trapped in a cycle of political uncertainty and economic underperformance that erodes its regional standing.

With growth barely above 2 per cent, a looming demographic crisis and an immigration regime unsuited to offsetting future workforce challenges, Thailand is in urgent need of pro-growth, pro-productivity reforms and public investment despite its strained public finances. These challenges are par for the course in any rich post-industrial country — but for a middle-income country in today’s international environment, they’re all the more daunting.

Thailand, Southeast Asia’s second-biggest economy, has to overcome development challenges as well as take on a larger regional leadership role within, and through, ASEAN. It faces these challenges in a period of renewed political uncertainty as the border crisis with Cambodia feeds into domestic politics ahead of elections scheduled for February 2026.

Preoccupied with domestic problems, it has been missing in action on the regional and international stage beyond the conflict with Cambodia. For decades, Thailand’s openness to trade and investment supported rapid growth, employment creation and rising living standards, anchoring it firmly in the upper middle-income tier. But local experts are sounding the alarm ever more clearly that high-income status is a pipe dream without deep structural reform. Reviving consumption and investment means building the confidence required for consumers to spend and the private sector to invest. Deregulation, institutional reform, and continued action on trade and foreign investment liberalisation alongside regional liberalisation efforts all form part of that agenda.

The missing ingredient is political stability — not just in terms of the ups and downs of inter-party competition, but the more basic lack of a settlement among different elite factions about the sanctity of the ballot box as a source of political legitimacy.

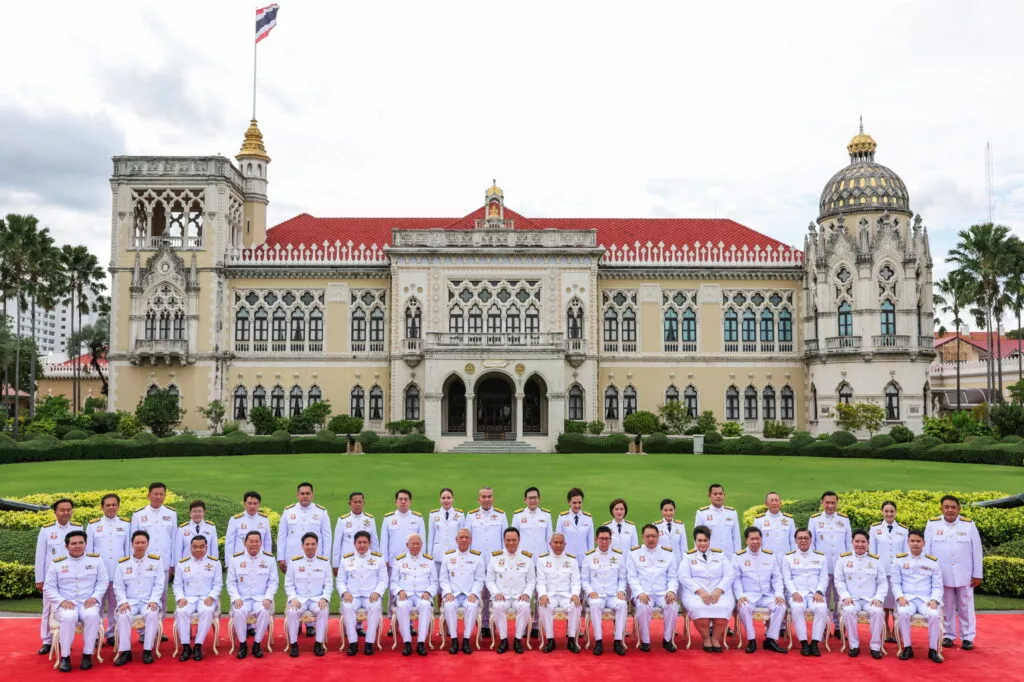

More than two decades of oscillation between elected populist governments and the (usually unelected) conservative administrations channelling military, royal and crony capitalist interests has undermined policy continuity, encouraged corruption, and incentivised public spending on redistributive boondoggles at the expense of pro-growth public investment, especially via an outmoded education system.

One critical missing ingredient in Thailand’s economic renewal is a functional democracy, one in which it is taken for granted that duly elected governments will be allowed to govern without intervention from so-called ‘tutelary powers’ — the military or palace. There’s no pro-growth inclination or agenda that has given other Southeast Asian authoritarian regimes some legitimacy in the past. And one potential force for political and policy renewal — the reformist People’s Party (PP), the latest incarnation of the Future Forward/Move Forward movement — has been consistently blocked from governing by Thailand’s conservative establishment.

These structural challenges were serious enough before the additional shocks of recent months: the hit from Liberation Day tariffs and the deterioration in relations with Cambodia. Even as long-standing structural impediments to economic dynamism remain unaddressed, the current government — a tense amalgamation of conservative and populist parties formed after the 2023 election to sideline a resurgent liberal camp — now has to navigate heightened uncertainty stemming from international economic and regional security developments. The US government under President Donald Trump is now trying to use the threat of punitive tariffs to force the Thais and Cambodians into a ceasefire deal.

This week we launch our annual EAF special year-in-review feature series assessing the past year across the region and looking to the year ahead, with Paul Chambers’ look at a dramatic political year in Thailand.

Chambers’ main message is that renewed territorial conflict along the Cambodian border has exacerbated political uncertainty as elections loom. A no-confidence vote destabilised the conservative-led caretaker government formed after the downfall of former prime minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra, herself removed from office by a hostile judiciary.

With elections called for February, looming over the disarray in the political arena is a newly resurgent military, which thanks to the border crisis with Cambodia is enjoying a boost in its popularity and ‘is increasingly acting independently of civilian preferences’, writes Chambers.

The government, under the leadership of the Bhumjaithai Party (BJT), has seen its popularity wane after a string of corruption scandals and a half-hearted response to the flooding that hit Thailand in recent weeks. A few electoral outcomes are possible in February’s polls, from an outright parliamentary majority for the progressive PP to a minority government headed by either PP or BJT. ‘Whether or not BJT leads’, writes Chambers, ‘will determine the prospect of constitutional reform’. Yet ‘efforts to expand Thailand’s political space, such as might follow a PP electoral landslide’, will likely invite a coup.

In short, Thailand’s ‘tutelary’ powers — the barracks, the bench and the palace — offer Thailand’s voters a Henry Ford-like proposition: you can vote for whatever you want, so long as it’s not systemic change. Tragically, Thailand’s political trajectory continues to hinge on choices made by entrenched veto players who have repeatedly overridden popular mandates. This systematic thwarting of the popular will condemns Thailand to chronic instability and economic underperformance, to the long-term detriment of its citizens and its regional and international standing.

The EAF Editorial Board is located in the Crawford School of Public Policy, College of Law, Policy and Governance, The Australian National University.

East Asia Forum