Thailand Uses Forest Act as a Shield under the “Salami-slicing Strategy” in its Attempt to Encroach upon Cambodian Territory

Thailand Uses Forest Act as a Shield under the “Salami-slicing Strategy” in its Attempt to Encroach upon Cambodian Territory

Thailand Uses Forest Act as a Shield under the “Salami-slicing Strategy” in its Attempt to Encroach upon Cambodian Territory

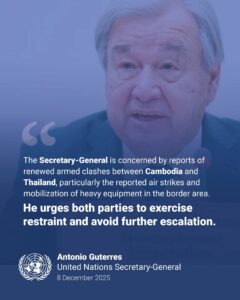

In recent times, the encroachment and expulsion of Cambodian civilians from Chouk Chey and Prey Chan villages—located in unsettled border areas between Cambodia and Thailand along the Cambodian side in Banteay Meanchey province—have caused shock, spread widely, drawing the attention of world leaders on the international stage.

The Thai government cannot conceal its malicious tactics. It is now evident that this nation is exploiting its “Forest Act” and environmental protection laws as the legal basis to claim disputed areas as Thai public forest lands, thereby forcing Cambodian citizens to leave and rendering them unable to live there. In reality, however, these areas are located within Cambodia’s legitimate sovereignty in accordance with the French–Siamese treaties of 1904–1907, the 1/200,000 scale map deposited at the United Nations, and the 2000 Memorandum of Understanding, which Thailand itself signed.

What is the purpose of Thailand’s Forest Act?

Thailand’s “Forest Act” was enacted in the 1940s–1950s with the original aim of conserving and managing national forest resources. It allowed the Thai government to declare any area with the characteristics of forest or undeveloped natural land as “state property.”

However, driven by expansionist ambition and perceiving its smaller neighbors such as Cambodia as weak and vulnerable, since the 1980s Thailand has shifted this law into a political instrument to serve its territorial expansion agenda-especially against Cambodia and Laos. The method is the so-called “Salami-slicing strategy”: seizing territory bit by bit over a long period of time, avoiding strong reactions from neighboring states.

Thailand has further used this Forest Act as a political shield in territorial disputes, claiming that areas where Cambodian farmers reside and cultivate are Thai forests. Cambodian citizens are then labeled as “illegal encroachers of Thai state forest.” In reality, Thailand has no solid legal documentation to prove sovereignty over such lands, but through aggressive maneuvering it exploits this law as pretext to evict Cambodian civilians and create “buffer zones” under its control.

This process begins with shifting lines on paper maps (at the 1/50,000 scale) and later moving those lines onto the ground to align actual territory with its unilateral claims. Ultimately, Thailand pressures Cambodia to accept these new border realities, backed by military intimidation. Thailand knows well that after the ceasefire, Cambodia has respected peace, avoided armed retaliation, and pursued diplomacy—because Cambodia seeks peace and an end to war, despite Thailand’s encroachment.

Are Chouk Chey and Prey Chan examples of the “Salami-slicing strategy”?

Both villages clearly lie within Cambodia’s legal sovereignty under the French–Siam treaties of 1904–1907. Cambodian citizens have long resided there as lawful Cambodian nationals. Yet Thailand has begun claiming these villages as part of a forest conservation area in Sa Kaeo province.

In fact, both Cambodia and Thailand know well that along unsettled border stretches there are also Thais living within Cambodian land. Cambodia has not yet protested or expelled them, preferring to wait for the joint border commission to complete measurements before resolving disputes. This approach reflects Cambodia’s civilized stance—valued and respected internationally—contrary to Thailand’s uncivil practice of sending officials to measure land, install signs, and expel Cambodian villagers in an inhumane manner.

This method mirrors Thailand’s repeated tactics along many of its borders: not using direct military forces, but manipulating domestic laws to alter reality on the ground. This is the most insidious form of encroachment Thailand has carried out.

In summary Thailand’s Forest Act is not truly about environmental protection—it is a disguised political weapon, serving expansionism, popularity, and territorial aggression against Cambodia. It can be called, in another sense, “the law of aggression against Cambodia.” The cases of Choek Chai and Prey Chan are clear and undeniable examples, as Thailand is attempting to redraw historical borders in its favor through uncivilized and imperialistic means, like in the primitive age, when there were no laws or customs, applying the way of life of a wild human society.

Such actions should be condemned strongly by the international community.

Nonetheless, Cambodia stands prepared as defender of its ancestral lands, safeguarding peace for its citizens by relying on international law and smart diplomacy to counter Thailand’s false “Forest Act” and its “Salami-slicing strategy” of encroachment.