Thailand’s Freeze on Peace: A Pause that Punishes Procedure

At noon on November 10, Thailand froze its own peace.

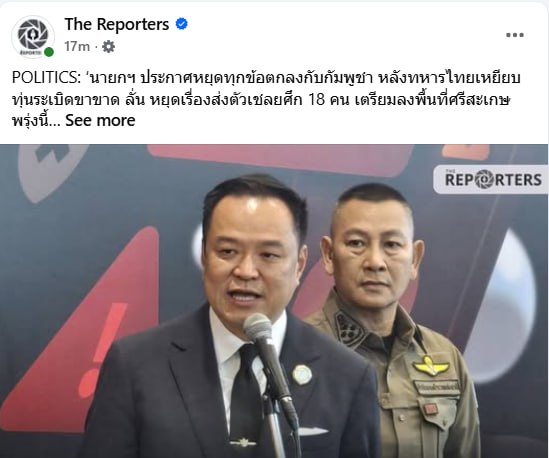

The order came directly from the Prime Minister: suspend the release of eighteen Cambodian soldiers and pause the implementation of the Thai–Cambodia Peace Declaration. The trigger was a landmine explosion in Huai Ta Maria, Sisaket Province, which struck a Thai patrol. Officially, the move was procedural. In reality, it was punishment dressed in legality — an act of emotion translated into administration.

The suspension, conveyed through the Ministries of Defence and Foreign Affairs, was framed as a “temporary suspension of compliance,” not a withdrawal. Yet, under international law, no clause within the Peace Declaration authorizes such a pause. This was not diplomacy—it was theatre. A gesture of sovereignty, performed for domestic consumption.

More tellingly, Bangkok chose to communicate its decision through the Interim Observer Team (IOT) rather than the Joint Boundary Commission (JBC). In doing so, Thailand shifted what could have remained a bilateral issue into a regional spectacle, compelling ASEAN to witness and document the breach. The protest was less a diplomatic message than a bureaucratic memorandum — a way to inscribe pain into regional record.

For the Thai military, this escalation also restores internal discipline. Ever since Lieutenant General Boonsin Padklang publicly resisted a ceasefire directive, cracks have appeared in the chain of command. Turning anger outward — toward a perceived external provocation — conveniently seals that fracture. The mine became a unifying symbol; the freeze, a declaration of unity disguised as outrage. Inside the barracks, it reads as loyalty; on paper, as leadership.

Yet the accusation underpinning the suspension defies logic. Cambodia has spent more than two decades clearing mines under the Ottawa Convention, earning global recognition as a leader in demining and humanitarian disarmament. To allege that Phnom Penh is laying new explosives is to accuse a surgeon of reopening the wound he has spent years healing. The claim serves not truth, but political expediency—a way to produce an external adversary at a time of domestic fatigue and criticism.

Across the border, Phnom Penh’s response has been one of procedural restraint. No counter-declarations, no retaliatory measures. Instead, Cambodia stays within the architecture of law — ASEAN mechanisms, demining records, and humanitarian verification. In this silence lies a kind of strength: a disciplined patience that contrasts sharply with Thailand’s performative urgency. When one side needs noise to survive politically, the other gains ground through quiet credibility.

The real cost, however, is economic. Each day of “temporary suspension” delays the reopening of border checkpoints, the resumption of demarcation projects, and the revival of cross-border tourism through Chong Chom. Theatres of sovereignty make for powerful headlines but fragile livelihoods. Communities along the border bleed from delays long before diplomats notice the wound.

Meanwhile, the media battlefield amplifies the divide. Thai platforms cycle through outrage and resolve; Cambodian outlets timestamp, verify, and move on. What was once settled in field tents is now contested in timelines. The first caption decides who is victim, who is aggressor.

In this choreography of bureaucracy, emotion, and optics, both states perform pain differently.

Thailand asserts deterrence through drama.

Cambodia asserts legitimacy through discipline.

One speaks through command.

The other through record.

Every border carries invisible wounds. In Sisaket, a soldier loses a leg; in Bangkok, a treaty loses one too. The difference is that the former may heal with medicine — the latter, only with memory.

A ceasefire can survive disagreement, but not humiliation. The strongest state is not the one that shouts its pain, but the one that documents it with dignity.