The ART of the deal lost in US–Malaysia pact

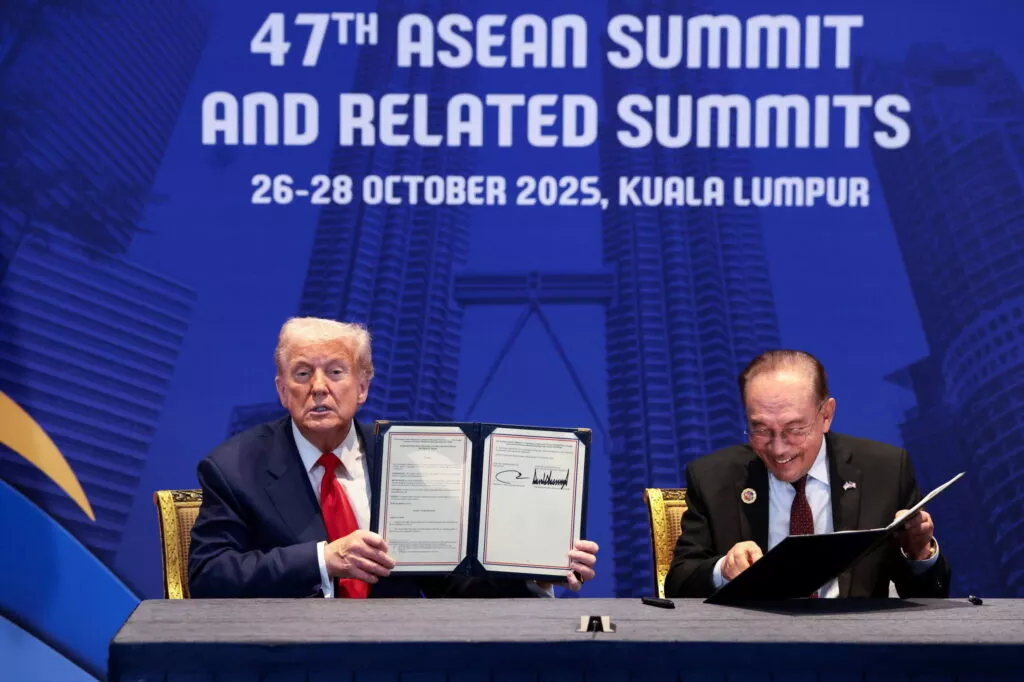

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim pulled off a diplomatic coup in welcoming US President Donald Trump to the ASEAN Summit in October 2025, his first since 2017. The centrepiece of the visit was the signing of the US–Malaysia Agreement on Reciprocal Trade (ART) on 26 October. But far from being reciprocal, the ART reflects coercive pressure and a hurried process between two countries with diverging views on trade and development.

Malaysian reactions to the ART have been swift and polarising. Political leaders valorise it as symbolising friendship and reciprocity while officials downplay the significance of its contents. Critics — among them former prime minister Mahathir Mohamad — decry a predatory deal that compromises Malaysia’s sovereignty.

The importance of context is lost in the debate. The ART was forged under duress by unequal parties with contradictory objectives, insufficient time to develop understanding and in violation of longstanding negotiating norms. There are some 48 provisions stating ‘Malaysia shall…’ but just three placing obligations on the United States. Washington has emphasised that it will not be bound by any trade treaty while Kuala Lumpur has already vocalised its ability to walk away.

The opaque and compressed dealmaking process is a recipe for unintended consequences and fragility. Prospective agreements are ordinarily subject to extensive stakeholder consultation but this deal went ahead without cabinet or parliamentary scrutiny, let alone wider engagement, with officials admitting that the agreement’s projected impacts have not been assessed. It does not provide stability for traders, investors and businesses, who are struggling to interpret what the ART means for Malaysia’s competitiveness within complex global supply chains.

Misunderstandings will be difficult to navigate. Unlike other treaties like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the ART does not contain any provisions for dispute settlement.

The ART represents a stark departure from Malaysia’s non-aligned and open trade and investment policies that have long supported its economic development and regional integration. Section 5 of the ART explicitly ties Malaysia’s trade and investment policies to US security interests and Washington’s strategic competition agenda. Section 3 also constrains Malaysia’s ability to negotiate preferential agreements on digital services with countries outside of ASEAN.

The deal does not create mutually beneficial trade and investment opportunities but legitimises Trump’s punitive tariff agenda. There is little reason for Malaysia’s exporters to celebrate a slightly lower tariff rate — now 19 per cent from 24 per cent threatened on 4 April 2025 — and a relatively minor selection of tariff-free goods when there were no tariffs a year ago. Malaysia’s market access concessions in return are modest as there were few barriers on US imports to begin with.

Malaysia’s concessions are not all without merit. The ART promotes greater recognition of standards, good regulatory practices and state-owned enterprise competitiveness, along with enhanced labour rights and environmental protections. Wider adoption of these provisions would support greater alignment with global best practice. But questions remain around why these goals must be pursued under coercive pressure, not through mutual agreement with neighbours and friends. And as the Trump administration slashes federal funding to food and pharmaceutical regulatory bodies, scepticism around the trustworthiness of US institutions as custodians of higher standards in these areas is warranted.

Malaysia is not alone in facing a revisionist US trade agenda, but by acting unilaterally in pursuing the ART, Kuala Lumpur has placed its perceived self-interest over collective prosperity. As ASEAN Chair, Malaysia engineered a collective rebuke of Trump’s tariffs and deescalated fears of retaliatory measures but undercut its own ability to negotiate on behalf of ASEAN by prioritising bilateral talks. As of November 2025, six of the 15 tariff agreements with the United States are with ASEAN countries, while the European Union is the only collective which has struck a deal.

Instead of pursuing rushed and unequal bilateral deals, Malaysia and ASEAN must instead defend open, trusted and rules-based trade and investment through collective action. While this is already happening, countries are pursuing bilateral agreements like the ART with greater urgency. There was much less fanfare earlier in the ASEAN Summit week over the ASEAN–China Free Trade Area 3.0 Upgrade Protocol’s signing, despite representing a more collaborative approach to tackling green economy, digital services and resilient supply chains.

Reanimating leadership discussions among RCEP partners and expanding the membership and depth of ASEAN-centred trade agreements are important steps towards reinforcing a system that supports mutually beneficial economic development.

The ART sets an unwelcome precedent for how Malaysia negotiates trade agreements and does not provide certainty for businesses. If this approach becomes the norm, it could irreparably damage Malaysia’s reputation as a free and constructive economic partner.

Stewart Nixon is Deputy Director of Research at Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS), Malaysia.

East Asia Forum